Turkish Dessert: Baklava

What is Baklava?

Where does the name Baklava come from?

Is Baklava a Turkish Dessert?

Types of Baklava

Baklava’s place in Turkish Culture

Tradition: Baklava Procession

Baklava in Turkey

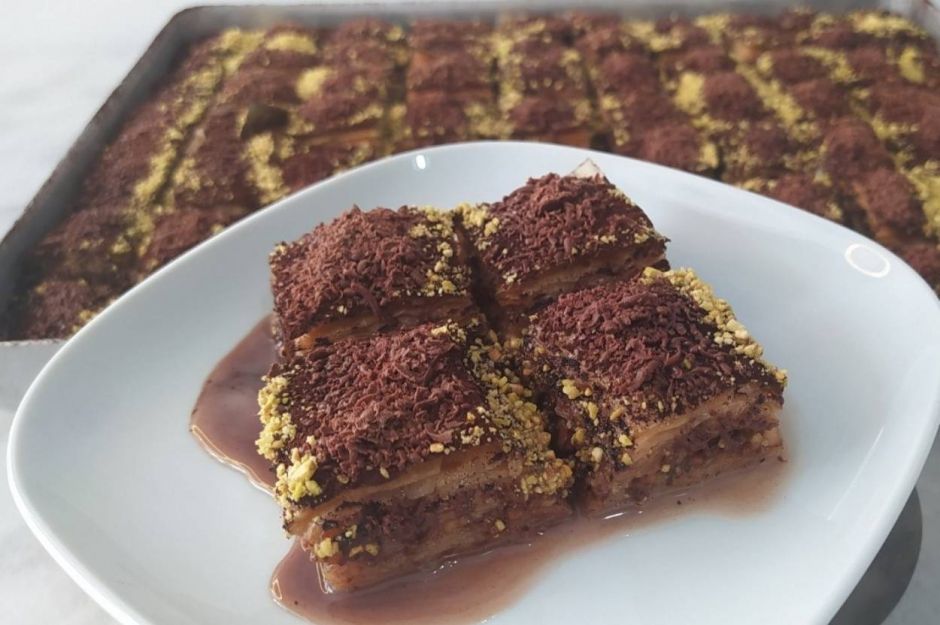

Baklava is a Turkish dessert. It is common in Anatolia, the Middle East and Rumelia. An average of 40-50 phyllo dough is at on top of a tray by oiling the spaces. Finely ground hazelnuts, pistachios, walnuts or almonds are sprinkled every ten pastries. After the tray is full, it is cut in the shape of a rhombus, hot oil is poured on it and given to the oven. After frying, the previously prepared cold syrup is poured slowly and left to cool.

Where does the name Baklava come from?

The word baklava is in usage as baklava or broad bean in old Turkish. In addition, the name “baklava” may have been derived by adding the Turkish verb suffix -v to the Mongolian word “bayla-” which means “to tie, to wrap”. However, the verb bayla- in Mongolian is also a quote from old Turkish. Contrary to popular belief, the word has no etymological connection with the Arabic word ‘bakla’.

Is Baklava a Turkish Dessert?

Almost all societies in the Middle East, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Balkans and the Caucasus; Turks, Arabs, Jews, Greeks, Bulgarians, Armenians introduce baklava as their traditional dessert. Considering that these regions were once part of the Ottoman geography, baklava is an Ottoman dessert. However, due to the perception of the Ottoman Empire as Turkish, especially Greeks and Arabs don’t accept this. However, the European Union Commission registered on 8 August 2013 that baklava is a Turkish dessert.

Types of Baklava

In old cookbooks, according to the material usage there are “ordinary baklava”, “baklava with almonds”, “baklava with pistachio (walnut)”, “güllaç baklava”, “melon baklava”, “baklava with cream”, “güllaç baklava with cream”. There are different types of baklava with names such as musanna (ornate, artistic) cream baklava, rice baklava, and fat-free baklava. People make dry baklava by keeping the baklava syrup thick and sugaring it. Moreover, the characteristic of dry baklava is that it can be in storage for a long time.

Baklava’s place in Turkish Culture

Baklava has a special place among the desserts made on certain days in Anatolia. In addition, it is an old tradition that is important for the girl’s side to send a tray of baklava and sherbet to the boy’s house at weddings. Today, Gaziantep baklavas and the masters grown here have gained a great reputation throughout the country in the last 40-50 years.

Tradition: Baklava Procession

In the tradition of the baklava procession, which emerged in the late 17th or early 18th centuries, baklava would go from the Palace to the Janissary Corps in the middle of Ramadan, as the sultan’s compliment to the soldier. Furthermore, a tray of baklava was prepared for every ten soldiers and lined up in front of the palace kitchen. After Silahtar Agha took over the first sini on behalf of the sultan, who was the number one janissary, each of the other sinisters was loaded by two soldiers. Moreover, the chiefs of each division were in the front, those carrying the baklava trays were in the back, walking out of the opened doors towards the barracks.

Baklava in Turkey

In Turkey, Gaziantep is the city famous for its baklava. Although the ingredient used in Gaziantep baklava is pistachio, this varies greatly geographically. In homemade baklavas, people use pistachios in Southeast Anatolia, hazelnuts in the Black Sea, walnuts in Central Anatolia, almonds in the Coastal Aegean, and sesame in Edirne and Thrace. Further, people can serve it plain or with ice cream.